What is mucus?

Most people find the mere thought of mucus gross and unpleasant. However, mucus actually has a very important role in the human body and often does not get the credit it deserves.

Mucus is a slimy, slippery fluid that is vital to bodily function and provides protection and moisture, which prevents the organs from drying out. Nasal mucus also contains enzymes and antibodies that kill off bacteria and help to fight infections and disease, making it one of the body’s first lines of defence against these harmful invaders. So we really do get a lot more from what’s ‘in there’ than what comes out than we realise.

To learn more about the fascinating functions of boogers and snot, read on…

Where does mucus come from?

Mucus is produced by mucus glands in the epithelium (lining tissues) of many organs in the body, as well as the urogenital, respiratory (nose, mouth, throat, sinuses and lungs) and gastrointestinal (digestive) tracts.

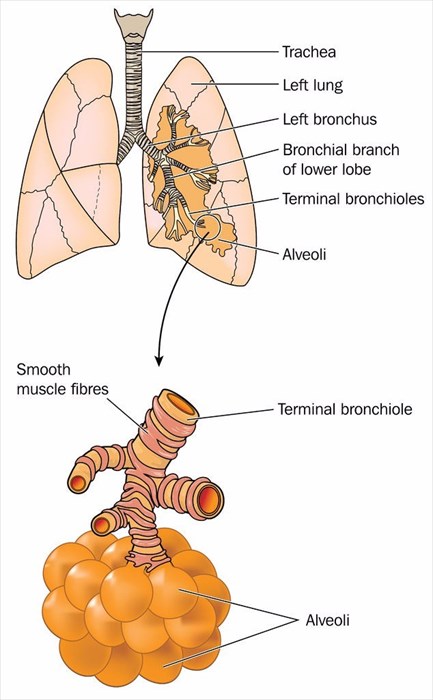

Mucus is secreted from two sites within the lungs. The first is the mucus-producing goblet cells within the surface of the epithelium, which make up a part of the airway’s lining. The second is the seromucous glands which are found in the connective tissue layer just beneath the mucosal epithelium. On average, these glands produce around two litres of mucus each day.

What is mucus made of?

Mucus is comprised of water, carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins1. It has a high water content which assists in humidifying the air that is breathed in as it passes. Mucus also contains proteins derived from plasma, glycoproteins (otherwise known as mucins) and traces of DNA as a result of cell death.

What does mucus do in the body?

Mucus has many important roles in the human body, however respiratory mucus has two important functions:

Filtering air

The sticky consistency of mucus helps to trap smoke, bacteria, dust particles and any other inhaled debris.

Fighting infection

The epithelial cells secrete proteins called defensins, which are considered a natural antibiotic. These, along with an antibacterial enzyme called lysozyme are found in mucus and help to destroy invading bacteria and prevent infections2.

How does mucus move in the body?

There are many different ways in which mucus is moved and transported throughout the body. Nasal mucus is moved by cilia in the nose towards the throat. It is then swallowed and digested in the stomach. This process is slowed when the weather is colder. This causes mucus to gather in the nose and drip – resulting in a runny nose.

Any particles that are larger than 4mm in diameter rarely get any further than the nose as they become trapped by the mucus formed there. Larger particles irritate the many sensory nerve endings found in the nasal mucosa, which stimulates a violent burst of air or sneeze to expel the irritants along with mucus.

When mucus moves further down the airway to the trachea and bronchi, the cilia found in those areas push the mucus towards the pharynx to be swallowed. Against the form of gravity, this upward movement is often referred to as the "mucus escalator" and is only noticeable when we clear our throats. When a large amount of mucus builds up, the cough receptors are stimulated and air along with mucus is forcibly expelled from the trachea.

The mucosal epithelium becomes thinner and changes in nature as it moves down the airway towards the lungs, there are no mucus-producing cells and very few cilia at this point. In the bronchioles, airborne debris is therefore removed by coughing or the macrophages in the alveoli. Macrophages are specialised white blood cells that form part of the immune system’s defence by engulfing organisms to be destroyed.

What is the difference between phlegm and mucus?

Both mucus and phlegm have a similar texture and are present in the body at the same time. The difference between the two is mainly classified by where they are produced. When excess mucus is produced by the respiratory system and coughed up, it is referred to as phlegm. Phlegm contains the bacteria or viruses present during an infection, as well as the white blood cells of the body's immune system that are involved in fighting it off. While phlegm is not considered dangerous, it can be harmful and clog up the airways when present in large amounts. It is usually coughed up in order to be expelled and may be accompanied by symptoms such as a runny nose, sore throat, and nasal congestion.

What do the different colours of nasal mucus mean?

- Normal healthy mucus is thin and clear.

- Thicker white mucus is a sign of congestion

- Greenish mucus indicates the presence of white blood cells which fight infection.

- A darker, yellow coloured mucus that is thickened is often accompanied by most illnesses.

- If the nose has become scratched or irritated it may produce a brownish or blood-tinged mucus. This colour is also common in upper respiratory infections such as sinusitis, pharyngitis, common colds, epiglottitis and much more. If you experience excessive nasal bleeding or frequently find blood in your mucus you should see a healthcare professional immediately.

When does too much mucus become a problem?

Even though excessive mucus is hardly considered a serious medical issue, it can be a nuisance and become uncomfortable, especially when it causes coughing fits or blocks the sinuses.

Some of the unpleasant symptoms caused by excess and thickened mucus production include:

- Coughing

- Sore throat

- Runny nose

- Sinus headache

- Runny nose

Should you experience any discomfort caused by excessive mucus production it is recommended that you see a healthcare professional for advice.

Resources

- Respiratory Care. July 2002. Physiology of Airway Mucus Clearance. Available at: http://www.rcjournal.com/contents/07.02/07.02.0761.cfm. Accessed [13/11/2017]

- The journal of clinical investigation. 15 March 2002. Antimicrobial polypeptides in host defense of the respiratory tract. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC150915/. Accessed [13/11/2017].

Other Articles of Interest

Bronchitis

At the turn of a new season it’s not uncommon for the body’s immune system to weaken, causing a dreaded cold or flu (influenza). Along with this condition, bronchitis may also develop...

Allergies

Allergies are something many people battle with but do not understand, this article explores all you need to know about allergies and how to deal with them...

Croup

Swelling in the vocal cords, voice box, bronchial tubes and windpipe is often as a result of croup. What is this condition? Here, we define the causes and types of croup...