We’re all familiar with branded labels which come with a standard warning along the lines of… ‘Excessive alcohol consumption may cause harm’. You might also be familiar with a headline or two promoting studies which have demonstrated some level of health benefit when alcohol is consumed in moderation. This has led to revised consumption guidelines on a governmental level. So, is alcohol harmful or isn’t it? How do consumers draw the right conclusions when there is so much conflicting information?

A research team from The University of Washington School of Medicine published a study looking at ‘the global burden of disease’ as it relates to alcohol consumption on 23 August 2018. Their systemic analysis looked at data from around 195 countries and territories between the years 1990 and 2016. The study was published in The Lancet, an international medical journal. (1)

The research, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, makes some rather stern statements. The bottom line? No amount of alcohol consumption contributes to overall optimum health. The study authors elaborate by stating that the health implications of even occasional drinking are in actual fact, greater than we think. An indulgence of just one or two drinks actually contributes to a decline in optimum health, which worsens as consumption increases.

The study acknowledges that some research has concluded that low levels of alcohol consumption (1 – 2 alcoholic beverages a day) can influence some degree of protective benefit when it comes to certain medical conditions, namely diabetes and even ischaemic heart disease. (2)

However, other studies appear to disagree, making the association between medical conditions and alcohol benefit a complex topic. (3)

When evaluating the factors which influence the effects of alcohol on health, one must consider how cumulative consumption influences a change in the body’s tissues, and most importantly, the organs, as well as the overall and specific physical consequences of acute intoxication, volumes consumed and drinking patterns. Measuring health effects in this regard is agreeably complex and somewhat challenging. This may be why studies have, to date, demonstrated differing results and findings. Few, if any, are looking at the cumulative effects of alcohol consumption over the lifespan of individuals or populations.

The researchers, whose recent report entitled ‘Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016’ appear to feel rather sure of their findings so far…

Assessing alcohol use as a leading risk factor for health decline

The research team consisted of academic professionals, medical researchers and various other professionals from at least 40 different countries. Their goal was to better understand the relationship between optimum health and alcohol consumption on a more global scale. To do this, the team needed to collect a large evidence base.

They therefore conducted an analysis of 694 data sources (extracting around 121 029 data points) looking at both individual and population levels of consumption in order to determine exposure estimations. The team also assessed around 592 clinical studies (extracting about 3 992 relative risk estimations) weighing up the risk of alcohol use in various ways. In total, around 195 different countries and territories were analysed from this data assessment, and distinctions made between genders and age groups. All in all, the team looked at data from around 28 million people and more than 649 000 registered cases.

The study assessment looked at alcohol in a broad context. The research does not make any distinctions between alcohol types – such as comparing spirits with wine or beer, for instance. This was largely due to a lack of information in this regard. The team needed to assess associations based on data that stipulated alcohol involvement, allowing for health outcome analysis. In this way, disease burden conclusions could be drawn.

The research team had to factor in patterns of alcohol use within different country populations and differences between genders. This helped to determine consumption per drinker averages which could be compared with associated health burdens. The study determined average consumption in terms of 10 grams of pure alcohol (ethyl) within a standard alcoholic beverage. This may be the equivalent of a small (100ml) glass of red wine (approximately 13% pure alcohol volume), or a 375ml bottle or can of beer (approximately 3.5% volume of alcohol), or 30ml shot of a particular spirit (approximately 40% alcohol volume).

Standard drink quantity averages are not, however, entirely consistent in every country. Quantities in terms of grams can differ, ranging from 8 grams to 10, 14 and even 20 grams per serving.

The team surmised that at least 2.4 billion of the world’s population could be categorised as ‘drinkers’ in the year 2016 (this is roughly 32.5% of the global population). Of these, nearly 63% (1.5 billion) were male.

In terms of health outcomes, the research team looked at current drinking prevalence in comparison to total avoidance or abstention, as well as consumption averages among drinkers in relation to attributable health decline and premature death.

The study thus found that drinking habits or patterns differed between genders and countries or territories. When looking at the average number of ‘standard drinks consumed’ (daily) within populations per 100 000, researchers listed the below findings from the year 2016 (all ages):

| MALES | FEMALES | ||

| Highest in... | Lowest in... | Highest in... | Lowest in... |

| Romania | Pakistan | Ukraine | Iran |

| Portugal | Iran | Andorra | Kuwait |

| Luxembourg | Kuwait | Luxembourg | Mauritania |

| Lithuania | Comores | Belarus | Libya |

| Ukraine | Libya | Sweden | Pakistan |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Bangladesh | Denmark | Timor-Leste |

| Belarus | Palestine | Ireland | Palestine |

| Estonia | Mauritania | United Kingdom | Yemen |

| Spain | Yemen | Germany | Tunisia |

| Hungary | Saudi Arabia | Switzerland | Syria |

Drinking prevalence among populations in 2016 (all ages assessed per 100 000 people) was:

| MALES | FEMALES | ||

| Highest in... | Lowest in... | Highest in... | Lowest in... |

| Denmark | Pakistan | Denmark | Bangladesh |

| Norway | Bangladesh | Norway | Morocco |

| Argentina | Egypt | Germany | Pakistan |

| Germany | Mali | Argentina | Egypt |

| Poland | Morocco | New Zealand | Nepal |

| France | Senegal | Switzerland | Syria |

| South Korea | Mauritania | Slovakia | Bhutan |

| Switzerland | Syria | France | Myanmar |

| Greece | Indonesia | Sweden | Tunisia |

| Iceland | Palestine | Iceland | Senegal |

Alcohol consumption does have an impact on overall health

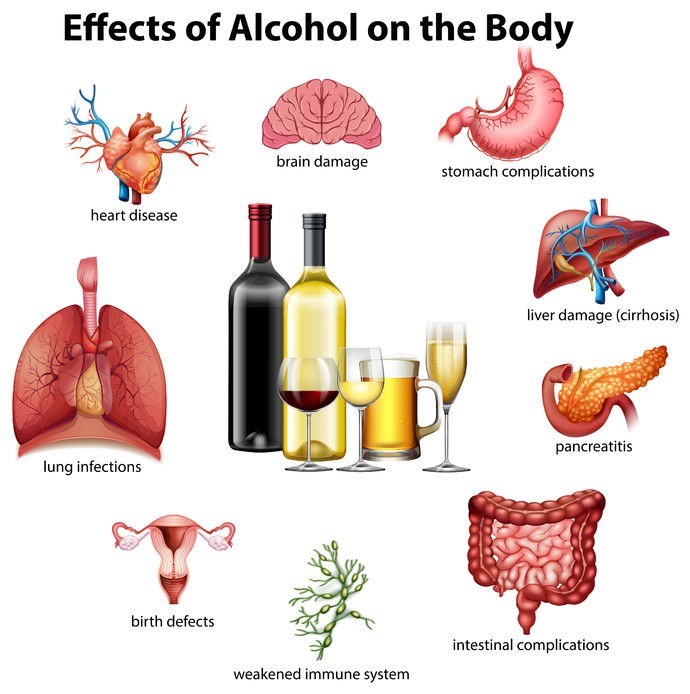

As a substance, alcohol is regarded as a depressant of the central nervous system, which can be absorbed rapidly within the stomach, small intestine and bloodstream. The liver metabolises alcohol but is only capable of doing so in small amounts at a time. Excess thus tends to circulate the body via the bloodstream. Thus, alcohol in the body is capable of affecting every tissue and organ to some degree or another, which can have a negative influence on a person’s overall condition.

The team of researchers was able to connect alcohol use to around 23 different adverse health outcomes. Individuals between the ages of 15 and 95 who consume at least 1 alcoholic beverage (daily) compared to non-drinkers appear to have an average 0.5% increased risk of developing at least 1 of these 23 health concerns. Initially, the risk may be small, but if consumption levels increase, so too does the intensity of the risk. This is fairly logical to understand.

Some of these concerning associations include:

- Cancer: Affecting the breast, liver, colon, larynx, oesophagus, oral cavity, lips and nasal passages.

- Cardiovascular problems: Ischaemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation (and flutter), hypertensive heart disease, stroke (ischaemic and haemorrhagic) and alcoholic cardiomyopathy.

- Diabetes mellitus

- Epilepsy

- Liver cirrhosis

- Pancreatitis

- Tuberculosis

- Lower respiratory infections

- Transportation- related injury (i.e. vehicle accidents)

- Intentional injury (i.e. self-harm or violence)

- Unintentional injury (exposure to harmful causes such as fire, heat, drowning, poisoning or mechanical contact)

Overall, alcohol raises the risk of disease development through a variety of mechanisms, all of which contribute to poor health. This includes:

- Damage to bodily tissues as a result of irritation and inflammation. (4)

- Interference with the body’s ability to absorb vital nutrients, such as folate which is required by cells to ensure ongoing health. (5)

- Hormonal fluctuations. (6)

- Effects on body weight due to excess calorie intake which may contribute to individuals being overweight or obese. (7)

- The enhancement of other harmful chemicals, such as those contained in tobacco products. (8)

- Hindering the body’s ability to break down and eliminate other chemicals and toxins. (9)

When assessing populations between the ages of 15 and 49, the research team found that overall, alcohol played a role in what they term ‘risk-attributable disease burden’, resulting in ‘disability-adjusted life years / DALYs). For males, the risk factor was measured at around 8.9%, and for females at 2.3% DALY associations.

The team noted that ‘risk-attributable disease burden’ for females, although much lower than that of males, did appear to increase with age. For males this burden showed increases well into their early to mid-sixties but appeared to decrease thereafter.

Any notable protective health benefits associated with low or moderate alcohol consumption however, were found to be minimal in comparison to the overall estimates determined in relation to attributable disease burden. The research team states that in relation to any protective benefit, future assessments should factor in the role of alcohol across the lifespan of a population if conclusive evidence is to be relevant enough.

Clear correlations between alcohol consumption and premature death

One of the key take-outs from the study highlight that in the year 2016, as many as 2.8 million fatalities across the globe were associated with alcohol in some way, shape or form. The study authors state that there are correlations which can be made between the consumption of alcohol and premature death, as well as the onset or worsening of major health conditions. The fundamental conclusion that was drawn by the researchers is that for a person’s health to not be adversely impacted in any way by alcohol consumption, the amount indulged in should be zero. No level of consumption, even if moderate or minimal should be deemed safe.

“Zero alcohol consumption minimises the overall risk of health loss,” says health metrics sciences professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine and senior study author, Dr Emmanuela Gakidou.

The research team tallied as much as 12.2% fatalities among males between the ages of 15 and 49, attributing their demise to alcohol involvement / association. The report lists attributable female fatalities at around 3.8%.

Death rates which the team attribute to alcohol consumption among populations in 2016 (per 100 000 people aged between 15 and 49) was:

| MALES AND FEMALES | |

| Highest in... | Lowest in... |

| Lesotho | Kuwait |

| Russia | Iran |

| Central African Republic | Palestine |

| Ukraine | Libya |

| Burundi | Saudi Arabia |

| Lithuania | Yemen |

| Belarus | Jordan |

| Mongolia | Maldives |

| Latvia | Singapore |

| Kazakhstan | Syria |

Alcohol, a global disease burden

The study ranked alcohol consumption as the 7th leading risk factor for significant loss of health, disability and death in the year 2016. Thus, the study authors appear to support the notion that increased consumption levels of alcohol, in particular, play a significant role in contributing to eventual health decline and the onset of serious disease.

As such, the team feels that consumption policy revision is required for all nations across the world. The primary purpose of this would be to lower consumption on a population level as much as possible. In an ideal world, zero consumption would be preferable. In reality, ‘the lower, the better’ is a more attainable approach if causal risks for various health conditions are to be sufficiently reduced.

It is suggested that ways in which authorities and policy-makers can influence lowering alcohol consumption rates include the implementation of further alcohol taxes, influencing the physical availability of alcoholic products (e.g. reduced hours of sale availability) and exercising more control over advertising (concepts and frequency).

Dr Gakidou feels that there is an “urgent need to overhaul policies”, specifically in areas where prevalence or higher fatality rates have been noted through the study. Lowering one’s consumption levels or refraining from altogether is something she strongly advises. It is her belief, based on the study findings, that even moderate consumption is in no way beneficial or “good for you.” This, she states, is merely a myth.

A zero level of safety conclusion does contradict general health guidelines, many of which agree on a 1 drink for women per day and up to 2 for adult males. (10) Even if the level of risk is small with moderate consumption, in all honesty, do populations actually indulge in the bare minimum?

Merely communicating messaging or consumption information that focuses on the health risks of “excessive use” may not be sufficient enough – certainly for the team of researchers who published these latest findings. Currently, moderate consumption is widely acceptable, and excess is communicated as potentially harmful to health. The authors of this study urge health authorities to re-think messaging and enable consumers to be better informed about the impact of alcohol consumption in the long-run.

References:

1. The Lancet. 23 August 2018. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)31310-2/fulltext [Accessed 28.08.2018]

2. US National Library of Medicine - National Institutes of Health. 11 February 2011. Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21343207?dopt=Abstract [Accessed 28.08.2018]

3. US National Library of Medicine - National Institutes of Health. May 2005. Cardiovascular risk factors and confounders among nondrinking and moderate-drinking U.S. adults: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15831343?dopt=Abstract [Accessed 28.08.2018]

4. US National Library of Medicine - National Institutes of Health. March 2010. Alcohol, inflammation, and gut-liver-brain interactions in tissue damage and disease development: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2842521/ [Accessed 28.08.2018]

5. US National Library of Medicine - National Institutes of Health. 8 November 2012. Folate, Alcohol, and Liver Disease: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3736728/ [Accessed 28.08.2018]

6. National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. October 1994. Alcohol and Hormones: https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa26.htm [Accessed 28.08.2018]

7. JAMA Network. 8 March 2010. Alcohol Consumption, Weight Gain, and Risk of Becoming Overweight in Middle-aged and Older Women: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/415737 [Accessed 28.08.2018]

8. National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. July 2007. Alcohol and Tobacco: https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa71/aa71.htm [Accessed 28.08.2018]

9. American Cancer Society. Alcohol Use and Cancer: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/diet-physical-activity/alcohol-use-and-cancer.html [Accessed 28.08.2018]

10. Health.Gov. Dietary Guidelines 2015 - 2020: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/appendix-9/ [Accessed 28.08.2018]