Before delving into whether coconut oil is indeed an ingredient that may be effective for weight loss, it’s a good idea to gain a basic understanding regarding its fat content. Yes, coconut oil does have high concentrations of fat, and there are divided opinions regarding whether it’s a ‘good kind’ or not.

Coconuts contain saturated fat (as much as 92%), but a natural variety (not artificially manufactured). All in all, the total amount of fatty acids in coconut oil only just falls short of 100%. Coconut oil also has about 6.4% monounsaturated fatty acids and approximately 1.5% polyunsaturated fatty acids. (1)

Thus, the sceptical camp may warn that coconut oil is quite fattening. How then, could it be good for weight loss? The pro-coconut oil camp will argue that the type of saturated fat and its mechanisms in the body make the difference between “no-go’ and ‘a little may do some good’.

Not all saturated fats are quite the same. Some occur naturally, while others have been exposed to manufacturing processes. There are several varieties of fat components in foods that are subjected to an artificial manipulation process known as hydrogenation. The addition of hydrogen atoms during a heating process alters the state of a substance, creating an often, unhealthy saturated fat product. Such products have gotten a bad reputation and for good reason. Many of these are associated with elevated cholesterol levels (low-density lipoprotein / LDL- cholesterol), heart disease and weight gain. The hydrogenation process effectively creates products which have a somewhat longer shelf-life for the consumer – an example could be vegetable oils added to spreads.

The pro-coconut oil camp would argue that the naturally produced variety, such as that found in coconut is not nearly as unhealthy as you might assume. Their argument breaks down the components of the fatty content and defines it by its component structure. Therein lies the difference…

Some fat in the diet is not a bad thing, contrary to past nutritional fads. Fatty acids should form part of any balanced nutritional plan, mainly because they help to provide the body with a sufficient amount of energy, as well as play a role in the building of healthy cell membranes and hormone function. Absorption of vitamins and body insulation are other perks of fat intake.

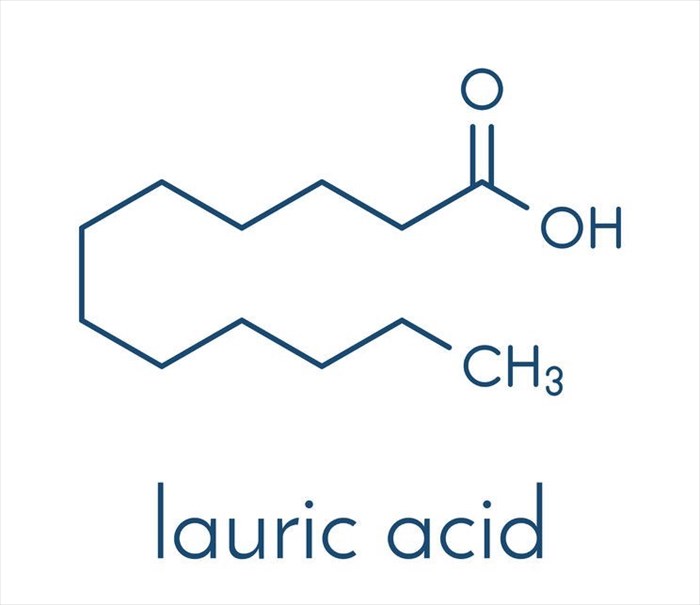

Lauric acid, a type of saturated fatty acid, is the main variation in coconut oil (making up nearly 50% of the concentration). Others are myristic and palmitic fatty acids. Lauric acid is converted to monolaurin (a monoglyceride also known as glycerol monolaurate) in the body. This substance is believed to have antibacterial and antiviral properties capable of eradicating lipid-coated pathogens from the body. Such pathogens may be associated with conditions like influenza, measles, and herpes simplex virus.

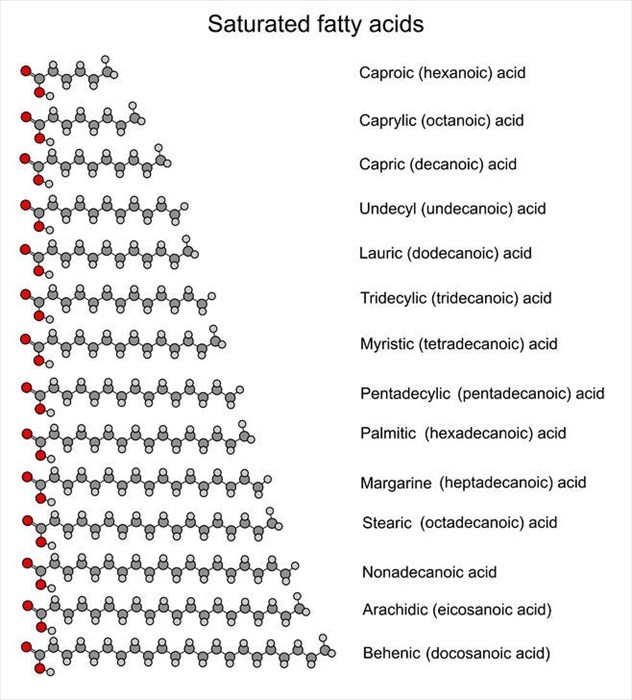

All fatty acids are structured as a chain of carbon atoms that comprise of hydrogen pairs. Thus, fat can be classified accordingly:

- Saturated fat: These fats contain a high number of hydrogen atom pairs which form a straight carbon chain. At room temperature, these fats are typically solid. Examples include butter and even coconut oil.

- Unsaturated fat: In these types of fats at least one of the hydrogen atom pairs is lost, causing molecules to bend at the site of a double bond. The less hydrogen pairs there are, the more molecules within this type of fat become bent. Fats with at least one missing hydrogen atom pair are known as monounsaturated fats while those with more than one missing pair are typically known as polyunsaturated fats. This type of fat is thus more typically found in a liquid state at room temperature – i.e. an oil.

The length of molecules (or ‘chain length’) and the degree of hydrogen saturation typically characterise the properties of fats and fatty acids. Classifications thus include (2):

- SCFAs / short-chain fatty acids: These have less than 6 carbon atoms.

- MCFAs / medium-chain fatty acids: These have between 8 and 10 carbon atoms.

- LCFAs / long-chain fatty acids: These have 12 or more carbon atoms.

- VLCFAs / very-long-chain fatty acids: These have 22 or more carbon atoms.

Chain length is associated with the melting point of a fatty acid. As the length increases, so does the melting point. Thus, solid fats tend to have longer chain lengths than liquid forms. Unsaturated fats tend to have a lower melting point than saturated varieties.

Coconut oil is classed as a medium- chain fatty acid (also known as an MCFA, MCT or medium-chain triglyceride with an average of between 8 and 10 carbon atoms). MCFAs can permeate cell membranes a little easier than long-chain fatty acids. This means that they are typically easier for the body to digest.

Medium-chain fatty acids are generally not stored in the body (within adipose tissues) as fat. This is because they are absorbed into the intestinal tract and then processed (metabolised) by the liver soon after ingestion. From here the carbon atoms are removed (processed) two at a time and converted into ketones (high-energy molecules / cells), followed by energy (adenosine triphosphate / ATP). These fatty acids thus help to stimulate metabolism in the body. The rate at which the body burns off energy is known as thermogenesis. This process is one of the main reasons why coconut oil is associated with weight loss.

Longer chain fatty acids are, by contrast, more difficult for the body to digest (break down) and can place a degree of strain on other organs such as the pancreas and liver. These are also stored as fat, contributing to fatty deposits (plaque) in the arteries (i.e. LDL-cholesterol, aka the ‘bad’ type). Once ingested LCFAs are transported through the intestines and into the bloodstream. Large fat droplets circulate the body before even reaching the liver for processing. Once reaching the liver, LCFAs are metabolised much slower than other types. This means that they can be more easily stored as fat in adipose tissues (fat cells).

So, are MCFAs a healthier variety? Perhaps – the debate over how to ‘define healthy’ remains. Certainly, LCFAs have a higher risk association with heart disease than MCFAs, but then such saturated fats have been better studied in human participants than the medium-chain variety. So far, consumption of MCFAs has been noted to enhance satiety, promote energy expenditure, and also prompt a reduction in overall daily food intake due to its higher fat concentration.

What about the impacts on cholesterol and heart health?

Current dietary guidelines estimate that no more than 10% of calories consumed in a day should contain saturated fat for energy purposes. (4) For the most part, the body doesn’t really need additional saturated fat through the diet. Higher consumption of saturated fats does elevate the total levels of cholesterol in the body, especially LDL-cholesterol. In doing so, the risk of cardiovascular disease increases – hence why fat restriction is a necessary consideration.

Coconut oil itself does not appear to contain any dietary levels of cholesterol. It has been suggested, however, that coconut oil can elevate levels of ‘good’ cholesterol (high-density lipoprotein / HDL-cholesterol), and this is another area where the difference between healthy and not comes in, irrespective of quantity percentages – for some experts that is. Other saturated fat products don’t appear to elevate HDL-cholesterol as much as coconut oil. It is theorised that the lauric acid content in coconut oil, which is considerably higher than in many other oil varieties, has something to do with such ‘good-cholesterol’ elevations.

Are these elevations a good thing though? Other experts appear less convinced and argue that the chemical components of the overall fat content of coconut is far more complex and requires much more intricate study – therefore conclusions shouldn’t yet be drawn. Some studies have even shown that coconut oil can indeed elevate overall levels of cholesterol, including LDL-cholesterol, even if to a lesser extent than other saturated fat products. (5) So, along with elevations in ‘good-cholesterol’, the bad kind can also be raised – something that wouldn’t be wanted.

If the fat content (MCFA) in coconut oil is not stored where it can cause direct harmful accumulation, contributing to ‘bad-cholesterol’ and heart disease, could it then be useful? If so, how much is good to consume, if at all? And how? Does the remainder of a person’s diet make up the ultimate difference between the ‘good’ and ‘bad’?

When looking at populations who frequently consume coconuts as part of a basic (and regular) diet, ‘healthy’ assumptions are easy to make – especially since many are not severely overweight populations or at particularly high risk for cardiovascular problems, when compared with those in other corners of the world. Face-value type assumptions are not reliable enough, however, and with limited study, even in this capacity, it is difficult to gauge the health benefits with any real surety.

It may be agreeable that a little coconut oil consumed over the short-term is not likely to spark serious illness. The bigger questions, however, are still unanswered.

Studies conducted have been small and limited with mixed results. Some have also merely been observational which cannot technically help to determine accurate risk markers for cardiovascular disease. Few have been conducted using human participants too. This is why opinions are very much divided when it comes to cholesterol and heart health. One study has surmised that coconut oil can raise total cholesterol levels (the good and bad variety), but not as much as butter can. The study does not appear to support regular use as a means to reduce risk of cardiovascular medical conditions. (6)

Many medical experts are likely to support the ‘sparingly’ or ‘limited use’ side of things. Coconut oil is flavoursome and an attractive ingredient to incorporate into a diet, however in terms of long-term effects, scientific studies appear to have concluded findings that are as divided as expert opinions. It has not been conclusively shown just how coconut oil directly impacts heart disease (or if it can help to lower risk of disease development) and its precise effect on cholesterol levels. Short-term effects (sometimes only spanning a few weeks) in this regard have been considered, but not so much the prolonged impacts of regular consumption. A precise cause and effect relationship is still not entirely clear, and this is something that is required in order to truly know if the fat content in coconut oil is either beneficial (in certain quantities) for the body or harmful. Instead of observational studies, more robust randomised controlled trials could possibly settle the debate. When it comes to research, study design is thus just as important as the questions being asked as it has a direct impact on the reliability of the findings.

Lipid profiles detailing cholesterol impact is just one factor to consider. Vascular function, blood pressure and inflammation biomarkers are just as important too. Differences could exist between coconut oil consumers and other oil consumption comparison groups (for example those using olive oil).

It’s agreeable, however, that coconut oil has some good components, but in terms of heart health, the jury is (technically) still out as to whether it’s any healthier to use it rather than other plant-based varieties like olive oil.

Breaking down fatty acids is complex, so what should the general public make of it? Many foods and substances contain a mixture of fatty acids, and since saturated fat is not considered an essential component for overall dietary health, it may be easier for the average person to merely limit their coconut oil intake to a basic daily percentage instead of trying to balance the differences in individual foodstuffs. Hence why most government health organisations recommend that daily intake be kept in the lower percentage range. Not only does this directly correlate with reduced cardiovascular risk, but also unnecessary weight gain that lends itself to all sorts of additional health problems in general.

References:

1. Wiley Online Library. 16 February 2016. Coconut oil - a nutty idea?: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nbu.12188 [Accessed 01.06.2018]

2. U.S. National Library of Medicine - National Institutes of Health. October 2008. Medium Chain Triglyceride Oil Consumption as Part of a Weight Loss Diet Does Not Lead to an Adverse Metabolic Profile When Compared to Olive Oil: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2874191/ [Accessed 01.06.2018]

3. University of Florida - IFAS Extension. Coconut Oil: A Heart Healthy Fat?: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/FS/FS28900.pdf [Accessed 01.06.2018]

4. Health.gov. Dietary Guidelines 2015 - 2020: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/executive-summary/ [Accessed 01.06.2018]

5. U.S. National Library of Medicine - National Institutes of Health. April 2016. Coconut oil consumption and cardiovascular risk factors in humans: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26946252?dopt=Abstract [Accessed 01.06.2018]

6. U.S. National Library of Medicine - National Institutes of Health. April 2016. Coconut oil consumption and cardiovascular risk factors in humans: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4892314/[Accessed 01.06.2018]