What is vitiligo?

Vitiligo is neither life-threatening nor contagious. It is estimated that vitiligo affects between 0.5 and 2% of the world’s population (1) with onset being most typical around a person’s mid-twenties.

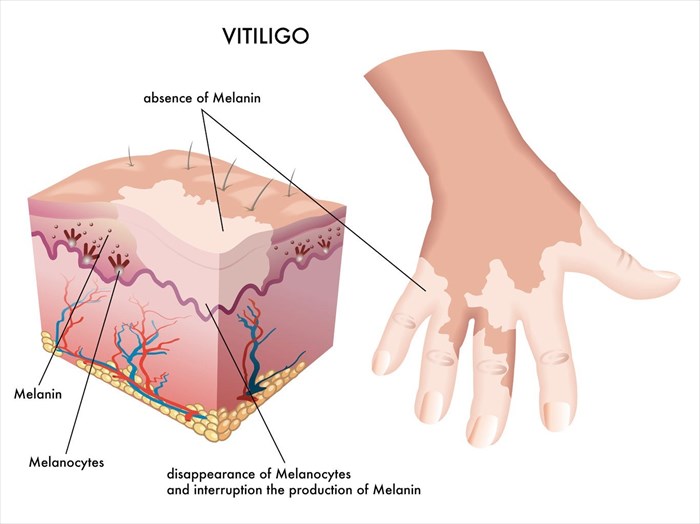

The condition commonly occurs in areas of the body that are most likely to be exposed to the sun, such as the face, limbs (arms and legs), feet and hands. It can, however, affect any portion of the body including the soft tissues inside of the mouth, nose (nostrils) and the mucous membranes of eyes, the ears and genitals. A section of hair (on the scalp or other hair producing areas of the body) may also begin to lose colour and turn white as a result of the condition.

Unlike other pigmentation disorders, the texture of skin in those affected by vitiligo remains unchanged and doesn’t develop scaling or other textures, nor is a loss of sensation experienced. Skin colour that is lost in patches or blotches does not typically follow a predictable pattern. The rate of colour loss and the extent to which the condition affects a person varies from one to the next.

Some may have just a few small patches, and for others, larger patches of skin colour loss develop in various spots on the body. Patches are often most noticeable on those with darker skin tones, but the condition affects all skin types.

A doctor cannot predict how much pigment a person is likely to lose, nor how it will affect the body. In some, colour loss occurs over a short period of time and then stops, remaining unchanged for several years. For others, the development of small patches appears to grow larger or newer macules develop. Although rare, it has also been documented that some skin affected by the loss of colour regains a portion of its natural pigment, even without treatment.

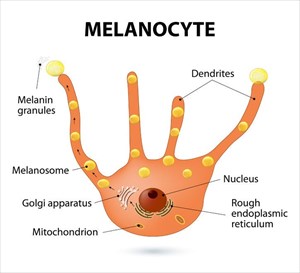

Many medical professionals generally regard vitiligo as an autoimmune disease of the skin (with a genetic association), whereby the body’s own immune system turns on itself, attacking tissues (in this instance melanocytes) and thus mistaking a portion of itself as a foreign body which needs to be destroyed. Around 15 to 25% of white European individuals with vitiligo have at least one other link, either personal or familial to an autoimmune disorder, such as rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune thyroid disease, type 1 diabetes, Addison’s disease, psoriasis, pernicious anaemia, alopecia areata or systemic lupus erythematosus. (2)

If no other autoimmune conditions are present, a person with vitiligo does not generally display signs of ill health or an inability to function physically.

The development of vitiligo patches can be extensive and for some, to the point of disfigurement. This can be life-altering on a psychological and emotional level, affecting self-esteem, causing social anxiety, withdrawal and depression.

Treatment for vitiligo targets the primary symptom and aims to restore lost colour. Currently there is no treatment available that can stop the loss of colour altogether and prevent the development of new patches. A cure is not yet available, but research is ongoing. Learning more about the condition and how to cope with caring for the skin is currently the best approach one can take once it is diagnosed.

Types of vitiligo

A doctor (most often a dermatologist) diagnosing vitiligo will typically classify a person’s condition into one of two primary group types:

1. Non-segmental vitiligo (NSV)

It typically begins with a rapid loss of skin colour, which then shows some respite for a while. It may be most noticeable on the hands, wrists, fingertips, feet, or around the mouth and eyes. Colour loss may pick up again after a period of time and then stop again (start-and-stop cycles). These cycles continue for the duration of a person’s lifetime, with patches tending to expand throughout the process. This makes patches more noticeable and typically become more apparent, covering larger areas of a person’s body.

There are various sub-types of vitiligo which are medically classified as non-segmental merely because they do not accurately fit the characteristics of segmental conditions (discussed below). Non-segmental sub-types are more commonly linked with clinical markers of inflammatory and autoimmune conditions.

Non-segmental sub-types which can be diagnosed include:

1. Localised / focal:

One or just a few patches (macules) appear on the body and are limited in location (occurring in just one spot or individually in a few portions of the body). One or two patches may also occur in a discrete area of the body.

2. Generalised:

A more common sub-type, patches are scattered in various places around the body. Generalised vitiligo has further sub-types of its own with specific characteristics affecting the body in various ways.

These sub-types are:

- Acrofacial: Patches occur mostly on the face (often around the mouth area), fingers (commonly the fingertips) and toes.

- Vulgaris: Patches are scattered with a widespread distribution around the body.

- Universal: A far rarer sub-type, extensive pigment loss occurs on the body (i.e. total or near complete depigmentation).

2. Segmental vitiligo

At least half of people with this type will lose some colour in their hair, including that which grows on the scalp or elsewhere, such as the eyebrows and eyelashes. It is also known to affect skin areas that are attached to nerves originating in the dorsal roots of the spine.

Segmental vitiligo is less erratic than non-segmental and is far less common too but responds better to topical treatment efforts. It is not associated with thyroid or other autoimmune conditions.

References:

1. US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health. October 2012. A review of the worldwide prevalence of vitiligo in children/adolescents and adults: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22458952 [Accessed 22.01.2018]

2. Genome Medicine. 19 October 2010. The genetics of generalized vitiligo: autoimmune pathways and an inverse relationship with malignant melanoma: https://genomemedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/gm199 [Accessed 22.01.2018]

Other Articles of Interest

Dermabrasion

An exfoliating technique which removes the superficial layers of the skin, dermabrasion can help to improve the appearance of skin. Here's all you need to know about the treatment procedure...

Birthmarks

What is a birthmark? Is it really as a result of unsatisfied wishes or cravings experienced by a mom-to-be during her pregnancy? What causes these discolourations? Learn more about birthmarks here...

Skin Growths (Benign / Non-cancerous)

The accumulation of skin cells and underlying tissue can cause a variety of flat or raised markings on the skin's surface. We take a look at some of the more common skin growths here...