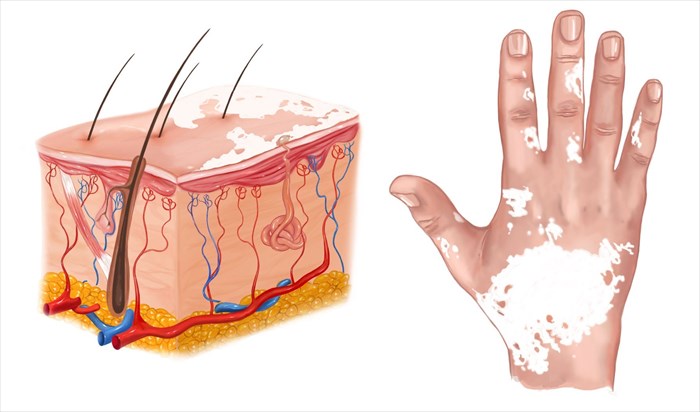

Signs and symptoms of vitiligo

Loss of skin colour is the primary characteristic trait of vitiligo. Onset is most typical in areas of the body that are generally exposed to the sun such as the facial area, neck, limbs, hands and feet. Vitiligo may begin as a tiny spot of lightened skin, which gradually becomes paler (as it grows) until it turns completely white (most often described as milk-white).

Patches can display more than one colour:

- Trichrome macules: Characterised as areas of white, light brown and normal skin colour – most frequently found on individuals with darker complexions.

- Quadrichrome macules: Marginal hyperpigmentation (i.e. affecting the skin tissues surrounding a follicle).

- Pentachrome macules: Characterised by a blue hue.

- Ponctué macules: Depigmentation which displays as tiny, confetti-like patches.

Patches are somewhat irregular in shape (but are commonly round, oval or linear), and are very distinctive (with obvious margins which may be convex / curved like the exterior of a sphere). These well demarcated margins or edges can become a little inflamed giving them a slightly red tone, which can cause some itchiness. It is, however, very rare for the affected skin to become itchy, dry or painful as a result of the condition. For most, patches do not display sensations. Affected skin areas are sensitive to sunlight (photosensitive), more so than pigmented areas of the body.

For many no other symptoms are present other than depigmentation that affects the skin and related structures.

General signs and symptoms of vitiligo can be broken down as follows:

- Patches of depigmentation (loss of skin colour or pigment – gradual lightening until milky white)

- Whitening or (premature) greying of hair (particularly the scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes and beard)

- Loss of skin colour in the mucous membranes / tissues that line the inside of the nose or mouth

- A change of colour or a loss of colour in the retina (inner layer of the eyeball)

There is no distinct way to predict the pattern of patches that develop, or if they will spread and to what extent spreading will take place. The type of vitiligo also comes into play here, providing clues. For some patches are small and localised, and may never increase dramatically in size. For others, patches appear to spread to other portions of the body. For some, spreading is a slow process, taking many years. For others, spreading occurs over a shorter period of time, sometimes in a matter of weeks before becoming stable for a few months or even years. Macules (patches) generally enlarge centrifugally (away from the centre or axis of the patch).

Normally, if the first patches that present are symmetrical, it is likely that the condition will be classified as non-segmental vitiligo. Sometimes a handful of small white dots develop and no more, other times larger patches develop and join others, effectively producing bigger areas of skin depigmentation.

Characteristic differences between non-segmental and segmental types of vitiligo include:

1. Non-segmental vitiligo

- Generalised characteristics: Macule depigmentation is typically symmetrical, occurring on numerous areas of the body and displaying a random distribution pattern. Areas most commonly affected include the face, extremities and trunk.

- Acrofacial characteristics: Patches of depigmentation mainly affect the distal extremities (fingertips) and the facial area. A related sub-type of this variation is known as ‘lip-tip vitiligo’ whereby patches affect the lips as well as the fingertips. Macules may later affect numerous other body regions.

- Mucosal characteristics: Vitiligo affecting the mucous membranes is most typical in body areas relating to the mouth and genital regions.

- Universal characteristics: All or almost all areas of skin are affected by vitiligo macules. Some small areas of skin or hairs may be partially affected. This sub-type normally occurs as a progression from generalised distribution patterns.

- Hypochromic characteristics: Also known as ‘vitiligo minor’, this variation is more common among individuals with darker complexions (although it remains a rare condition). Pigment loss may result in areas of skin that are paler than other surrounding areas, but without clear delineation. Macules are more commonly found on the scalp and trunk of an affected person.

2. Segmental vitiligo

The distribution of vitiligo patches typically follows the trigeminal nerve - the fifth cranial nerve which is linked with sensation in the facial area, as well as with functions of biting and chewing. The pattern of macules / patches is generally described as dermatomal or quasi-dermatomal and does not cross the midline of the body. Macules very rarely spread beyond the affected dermatome (i.e. area of skin that is supplied by a spinal nerve, relaying sensation), typically stabilising within about a year of formation.

This type of vitiligo most often develops during childhood and can sometimes involve the breaking down of melanin producing hair follicles as well (leukotrichia), resulting in colour loss (i.e. white hair).

When multiple areas of the body display unilateral or bilateral macule distribution this is sometimes referred to as ‘pluri-segmental vitiligo’. Distribution also stops at the midline and typically follows a dermatomal pattern.

Associated symptoms include:

- Low self-esteem

- Mood disorders (anxiety or depression) and associated behaviours and symptoms

When to consult a doctor

Losing colour in the skin, eyes or hair can be worrying for most. Many may not seek medical treatment since the condition does not present any particularly bothersome characteristics, like physical pain or inflammation and other sickly symptoms such as nausea or vomiting.

The appearance of skin changes alone does indicate something which should be checked. There are other conditions that can resemble or be mistaken for vitiligo. In order to determine an accurate diagnosis, a medical doctor (dermatologist) will need to conduct a thorough evaluation. Medical doctors and dermatologists in particular, are able to advise on treatment for the condition, which involves ways to potentially slow down the discolouration process or even return some pigment to areas where it has been lost.

Conditions which can be mistaken for vitiligo include:

- Nevus depigmentosus: A depigmented or hypopigmented area of the body is present at birth or appears in the first years of life. The condition is a form of cutaneous mosaicism (where the cells within the affected infant or child are comprised of two different types of genetic makeup) and clones of melanocytes (melanin producing cells) are altered and become defective in their pigment producing functions.

- Halo nevus (Sutton nevus): A mole (or moles) surrounded by an oval ‘halo’ of depigmentation.

- Tinia versicolor (or pityriasis versicolor): These white patches on the skin are normally caused by a fungal (yeast) infection, and unlike vitiligo have a fine dry and scaly appearance. The condition can be worsened by oily skin. Those residing in hot and humid climates, or who have poor hygiene habits can also experience worsened conditions. Common sites of infection where patches develop are the upper trunk and chest.

- Pityriasis Alba: A white patch commonly occurs on the face and sun exposed areas. The condition is usually self-limiting in nature and is closely associated with eczema (atopic dermatitis), a skin condition that results in an itchy scaly rash.

- Piebaldism: Present at birth, this is also an autosomal condition which displays the absence of melanocytes in affected skin areas. Normal pigmented and hypo-pigmented patches will be present with this congenital condition. Typically affected areas of the body include the torso, extremities, forehead and chin.

- Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: Rounded or tear shaped patches (small white spots) that occur in multiple areas of the body following exposure to sunlight (sunburn). The limbs (namely shins and forearms) are commonly affected. This condition affects approximately 80% of people over the age of 70.

- Scleroderma: This condition can result in shiny, hardened patches on the skin.

- White scars: A scar which follows an injury produces a white (or lightened) marking on the skin once healed. These can resemble vitiligo because melanocytes have been destroyed and thus cannot produce pigmentation to restore the skin colour.

- Chemical leukoderma: Exposure to chemical substances can lead to hypo-pigmented skin patches which can resemble vitiligo.

- Drug induced leukoderma: Certain medications can cause a loss of pigment that may resemble vitiligo. These include:

- Some potent topical and intralesional corticosteroids

- BRAF inhibitors: dabrafenib and vemurafenib (used in the treatment of melanoma skin cancer)

- Programmed death receptor inhibitors: nivolumab and pembrolizumab (used in the treatment of melanoma skin cancer)

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, gefitinib and imatinib (used in cancer therapy)

- TNF inhibitors: adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab (used to treat autoimmune and inflammatory conditions)

- The transdermal methylphenidate patch (used in the treatment of ADHD)

- Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: This is a rare variant of early-stage mycosis fungoids (MF), also known as Alibert-Bazin syndrome, a disease wherein lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) become cancerous and affect the skin. It typically affects individuals with darker skin tones and results in white patches with mild scaling and atrophy.

- Leprosy: A bacterial infection of the skin, light coloured patches can develop, but these are accompanied by a loss of hair and sensation to the affected areas.