The precise mechanisms of stretch mark formation do not appear to be very well understood and are still seemingly undergoing research to determine the more intricate details.

It is believed that the formation of stretch marks is multifactorial and includes the following factors:

- Physical changes to the body (wherein the skin experiences increased tension)

- Skin structure alterations (with changes to collagen and elastin fibres)

- Hormonal influences

Physical changes in the body that lead to stretch marks

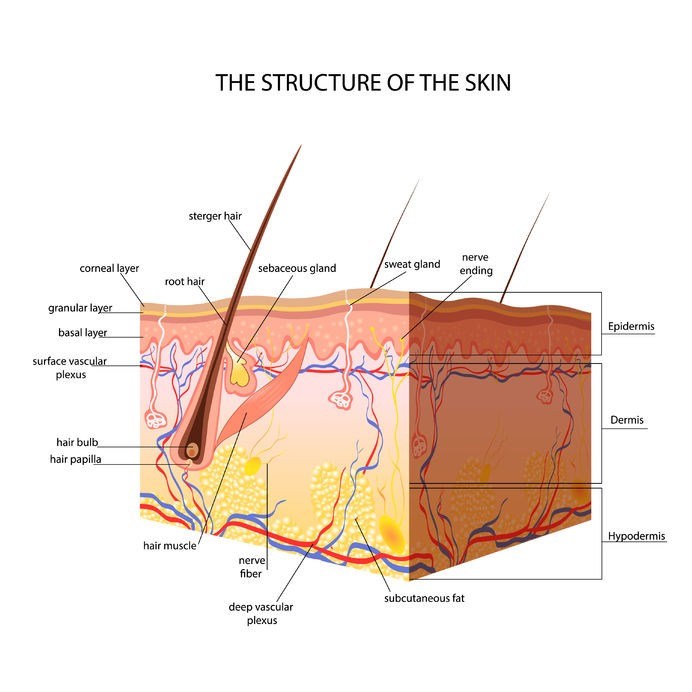

Basically, the epidermis (the visible outer layer of skin) which contains numerous sheets of cells has a basket-weave appearance with well-formed rete ridges (these are the downward projections of the epidermis which interlink with superficial dermis layers). This outer layer of skin functions as the protective barrier for all of the underlying tissues of the body. Within the epidermis is the natural pigment, melanin which contains pigment-producing cells called melanocytes. These cells are the structures responsible for a person’s skin colour.

Below the epidermis is the dermis (mid-layer of skin) which is made up of evenly spaced collagen and elastin fibres that are positioned parallel to the epidermis and help to provide the skin’s layers with strength, pliability and elasticity. Beneath this is the subcutis / hypodermis (subcutaneous tissues) which consists of connective tissues and fat cells.

Underlying tissues and cells which rapidly expand cause these layers of skin to stretch beyond their normal capacity

.

Skin structure alteration that cause stretch marks

Stretched skin alters the normal functions of the skin’s structure, causing…

- Reduced migration and generation of fibroblasts (cells which help to synthesise collagen)

- Reduced collagen fibres and fibronectin gene expression (glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix that play a role in cell adhesion, as well as the growth, migration and differentiation of cells)

- The thinning of tropoelastin-rich fibrils (an elastic protein in fibres)

- Disruptions in the skin’s elastic fibre network

The physical stretching and structural alterations of the skin then results in an inflammatory reaction and brings about the pink / red or even violet (purplish blue) hues associated with the initial formation of stretch marks. The associated inflammation disrupts the normal processes of the small white blood cells in the dermis and stationary phagocytic cells (cells which normally ingest harmful foreign particles, bacteria or cells which are dead / dying) within the connective tissues. Inflammation also results in swelling (oedema) of the skin and erythema (redness of the skin and mucous membranes).

Inflammatory responses due to overstretching change the appearance of the skin but fade with time and begin to ‘settle’. During the fading process the epidermis thins out, excessive degranulation occurs affecting mast cells (a type of white blood cell involved in immune system response), causing them to break down, dermal layers lose elastin (due to increased activity of the enzyme elastase which breaks down elastin) and dense collagen fibres form – with the end result being scar tissue. Once at this stage, stretch marks are at their most difficult to remove and can become permanent.

Hormonal influences in the development of stretch marks

- Increases in oestrogen, androgen and glucocorticoid receptors – which steroid hormones like cortisol bind to.

- Elevations in serum cortisol (e.g. corticotrophin-releasing hormone / CRH), resulting in increased protein catabolism (the breakdown of proteins into amino acids and other compounds), which inhibits the formation of collagen and also results in changes to elastin fibres.

- Reduced relaxin serum levels (a hormone secreted by the placenta, which helps to prepare a woman’s uterus for labour / birth), which decreases the production of collagen and increases the breakdown of the protein.